Secrets locked up

Are loaded on my back

And it weighs me down

Stanza from Exo-Politics from the album Black Holes and Revelations by Muse, lyrics by Matt Bellamy

My husband gave me a couple of Muse CDs for Christmas, which I have been listening to obsessively since I received them. One of my favorite songs from the album Black Holes and Revelations is Exo-Politics for its gritty, rooty sound. The stanza I’ve quoted above is from the song, which is about alien overlords taking over Earth, but it is apt for the topic I want to discuss in this post: Historical trauma.

Historical trauma is trauma that has occurred in generations past but that continues to affect today’s generations. The effects can be psychological, physical, economic, social, geographic, and institutional.

Let me give you a personal example.

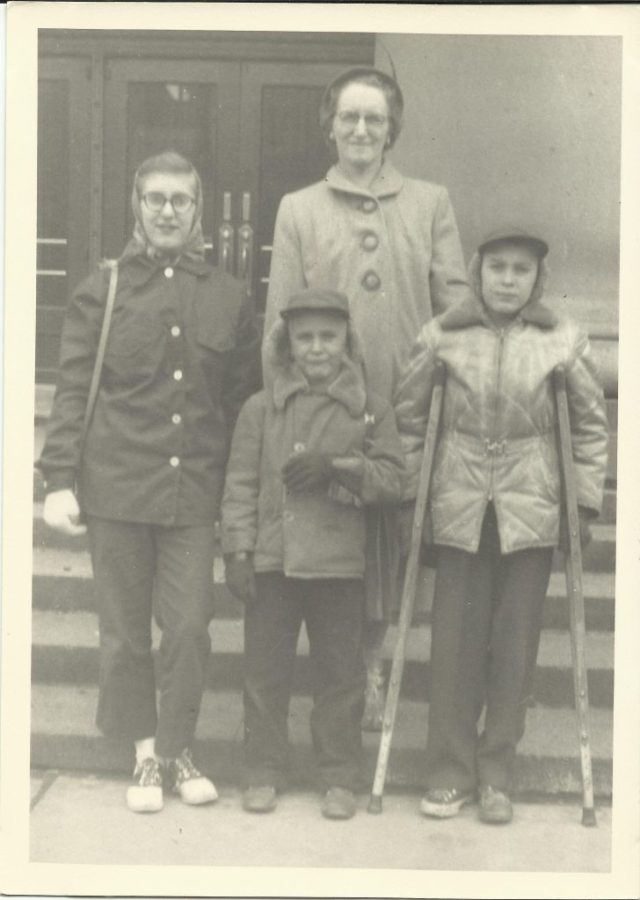

Both of my parents had paralytic polio as children. My mom was only 5 when polio struck on her first day of kindergarten. As she tried to get out of bed, she fell on the floor. She was treated at the Sister Kenny Institute in Minneapolis. The treatment was aggressive and painful physical and heat therapy. Because of this, she threw a fit one time and was put into a closet as punishment for the outburst.

Her parents were told she would die. Her prognosis was then upgraded to, “She’ll be in a wheelchair for the rest of her life, unable to walk,” then upgraded again to, “She’ll be on crutches the rest of her life.”

She had numerous surgeries to deal with the effects of polio on her most-affected leg, with metal pins being inserted. While the surgeries helped and allowed her to walk without crutches, her right leg was shorter than the left, with the muscles being atrophied and her foot having a permanent drop to it. This foot was also smaller than the other, which necessitated her buying 2 pairs of shoes of different sizes so that she’d have one to fit each foot.

Because she got polio at the height of the polio epidemic (60,000 children infected in 1952, the year my mom got it), the hospital wards were filled with sick children, something my dad also confirmed. He said that beds were shoved next to each other, with no space between them, because there were so many suffering from the disease. My mom watched a child die in front of her.

Imagine being a young child who is dealing with a serious disease and the medical professionals, who are there to purportedly help you, stick you in a dark closet, give your parents the worst prognosis ever (though it may have been realistic), and you’re witness to another child’s death.

Now, go home to an abusive father, who blames your mother for giving you polio and is suffering from his own undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder from serving as a Marine in the Pacific Theater during World War II. You’ve also got to go back to school, where the other children tease you because of your short leg, calling you “Hopalong Cassidy.”

Think about how these experiences would color your entire world view.

Now bring children into the picture.

Because my mom couldn’t run, once she had me and my siblings, we had to stick close to her because she couldn’t chase after us if we were in danger. To this day, I am more tentative about exploring my physical surroundings than I’d like to be.

Because her father was verbally abusive, my mom was not good at conflict resolution. She yelled, we children were supposed to quietly take it … no talking back or disagreeing with her. The result? Children who became adults that have difficulty broaching topics we think will result in conflict.

She also was proud to have spanked me with a hairbrush or ruler until these items broke. While I’m not sure if my grandfather was physically abusive, other than once throwing a book at my mom, the fact that my mom would spank me until a hairbrush … a hairbrush! … broke indicates that she dealt with physical abuse, too. For me, this meant further avoidance of conflict and a fear of making people mad.

This is how historical trauma develops, passing from one generation to the next. And my family has not had nearly the extremes in historical trauma that Native families, families who have been enslaved, or families who have survived genocide have dealt with.

When I was younger, there was a lot of talk about how to break the cycle of abuse, trying to prevent someone who has been abused from abusing their own children.

Prior to becoming a parent, I had made a couple of conscious decisions. I was not going to spank my children with objects (I very rarely spanked them at all, and then only a couple of swats with my hand) and I was going to raise them to become independent adults who made a contribution to society. I did not want them to feel they had to hover around me as my mom expected me to do with her.

While I was successful in these endeavors, I still have issues regarding handling conflict. I suspect I’ll be working on this the rest of my life. My hope is that I didn’t pass this along to my children.

I think becoming conscious of the historical trauma suffered within a family, learning as much as you can about its details and how it affected your relatives, and making a concerted effort to personally heal from that trauma and not mete out its negative effects on others is the key to coping with historical trauma.

Author, professor, and historian Anton Treuer, whose father was a Holocaust survivor and mother is an enrolled member in the White Earth Ojibwe Nation, recently shared an article on his LinkedIn timeline called “Trauma Is Not Your Fault, But Healing Is Your Responsibility” by Brianna Wiest.

In the comments on Treuer’s post, someone said that healing from trauma ought to be the responsibility of society as a whole.

Wiest provides plenty of reasons why the responsibility of healing from trauma falls to us as individuals, but this is the most relevant in terms of the idea of waiting for society to heal us:

“Healing is our responsibility because if we want our lives to be different, sitting and waiting for someone else to make them so will not actually change them. It will only make us dependent and bitter.”

Yep. You could waste your entire life waiting for society to change enough to help you heal and it’s not going to be as effective as you taking healing into your own hands. That doesn’t mean we just let society off the hook for changing so that a societal-level trauma continues to hurt people. It might mean that as you work on your individual healing, you also look for ways within your control that will help heal the larger society. It might mean raising your children as best you can without continuing the trauma. Or it could be working on policies that change the unfair, unjust laws that criminalize poverty or keep people of color from having the same opportunities as whites. Or it could mean contacting your legislators to pressure the U.S. government to stop holding immigrants in cages. (Imagine the trauma this is causing at this moment in the name of the American people.)

I think that one of the critical factors in my being able to move forward through the historical trauma within my family was learning the history behind my parents’ experiences with polio and my grandpa’s war service. Knowing the difficulties they went through helped give me the distance I needed to understand that their behavior toward me wasn’t personal. It was a result of their trauma. I could let it go, rather than loading it on my back and allowing it to weigh me or my children down.