Last Monday, I visited my county law library. It’s a fairly small room in the courthouse, with lots of tall shelves for books filled with higher court decisions and laws.

The earliest books seem to be these Minnesota Reports that contain cases decided in the Supreme Court of Minnesota. The publishing date of Volume I is 1877, but it contains cases between 1851 and 1858, when Minnesota was still a territory. (Minnesota became a state in 1858.)

When I was taking my paralegal training, my instructor, Angela Crossin, suggested we pay a visit to a law library. We did our research for class assignments online using Westlaw and our state’s legislative sites to find specific state laws, but before the internet, these law libraries were critical to conducting research on cases. This is where attorneys and paralegals could find the precedent and laws needed to argue cases.

I had an opportunity to chat with the law clerk in charge of this self-service library. Because so much legal research is now done online with Westlaw, LexisNexis, and other legal sites, there is really no need for the books in this library. In fact, the library has a computer with a subscription to Westlaw for the public to use. This law library is quieter than a church, so it’s a great place to randomly look at books from the stacks and think.

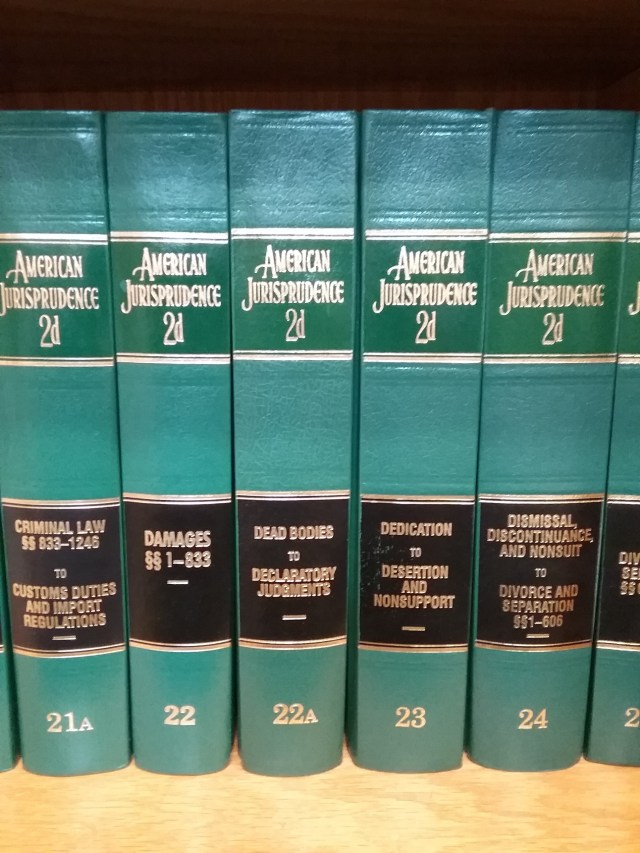

Just looking at the spines of books is entertaining, like this shelf of American Jurisprudence volumes.

Note the subjects printed on the spine, specifically “Dead Bodies to Declaratory Judgments.” Someone had to make the decision to split the volumes so that “Dead Bodies,” a real show-stopper of a subject heading, would appear on the spine.

Aside from the books and the computer with a subscription to Westlaw, the library also contained a computer devoted to letting people print legal forms, as well as a few subscriptions to current legal periodicals.

One of these, Bench&Bar of Minnesota, the March 2021 issue, caught my attention due to a specific article: “What Would a Discipline Office Do? Examining the high-profile complaints against election attorneys from a lawyer regulatory perspective” by William J. Wernz.

Last week’s blog post, “Observations on Ethics and the Law,” was obviously on my mind when I spotted this article. In my post, I wondered why so many lawyers and politicians who trained as lawyers associated with the former president seemed to be breaking the American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct and not being held to account.

In the Bench&Bar article mentioned above, Wernz gives a full analysis of what it takes to discipline a lawyer for breaking the Model Rules, using the actions of several of the lawyers I discussed in my blog post as examples, including Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, and Josh Hawley. The process is a lot more complicated than one would think. (William J. Wernz, “What Would a Discipline Office Do?” Bench&Bar of Minnesota, March 2021.)

For one, Wernz points out that attorneys have a right to free speech, so this has to be taken into consideration during a case related to disciplinary proceedings. (pg. 28)

In addition, if it’s too easy to discipline a lawyer for ethics violations based on what they say, the disciplinary procedure could be used to unjustly punish lawyers for political reasons. If a lawyer were to speak in favor of civil rights and an anti-civil rights politician wanted to punish that person, they could seek sanctions or disbarment. (pg. 28)

According to Wernz, a legal disciplinary body is going to look for a civil or criminal suit against an attorney to bolster a discipline case. So, Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani being sued by Dominium, the voting machine company, for defamation related to their statements regarding machines manipulating the presidential vote in the last election, is the sort of litigation that a disciplinary body will look at in determining sanctions. (pg. 29)

Wernz provided a thorough discussion of considerations to be made in disciplinary cases related to specific Model Rules. Like other legal cases, disciplinary cases against attorneys require significant investigation, which means it takes time to build such cases.

Even so, Wernz points out that if “a lawyer’s continued authority to practice law during discipline investigation and proceedings poses a substantial threat of serious harm to the public, the discipline agency may petition the state Supreme Court for an immediate suspension.” (pg. 30)

With news this week of the suspension of Rudy Giuliani’s license to practice law, the Supreme Court of the State of New York did indeed find that Giuliani’s “conduct immediately

threatens the public interest and warrants interim suspension from the practice of law.” Attorney Grievance Comm. for First Judicial Dep’t v. Giuliani (2021) https://www.nycourts.gov/courts/ad1/calendar/List_Word/2021/06_Jun/24/PDF/Matter of Giuliani (2021-00506) PC.pdf. (This document is worth reading in its entirety, but especially the latter portion of the conclusion starting near the end of page 30 with this sentence: “The seriousness of respondent’s uncontroverted misconduct cannot be overstated.”

It’s heartening to see from Wernz’s article in Bench&Bar of Minnesota and the decision to suspend Giuliani’s practice of law that the legal profession is concerned about the ethics of attorneys.

Take the opportunity to visit your local law library. They are there to serve the public.

Discover more from Without Obligation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.